A Conversation Between: Jim Biddulph & Matthew Raw

As we move into an evermore-digital world, there is an argument that we are creating less artefacts and evidence of the ways in which live for future archaeologists to discover, while quite literally losing touch with our immediate, and more remote, tactile surrounding in the here and now.

Matthew Raw

The relative durability of ceramics makes them a highly useful tool in piecing together human history, something that we explored in our The Making of Ceramics film, which featured designer and maker Matthew Raw and his colourful tile intervention at Seven Sisters station, London.

Matthew has a long association with and appreciation for the material, having been introduced and taught about it in some detail on the BA Wood, Metal, Ceramics and Plastics course at University of Brighton on the early 2000’s. His love for the material grew during a 6-month residency at Guldagergaard International Ceramic Research Centre, Denmark in 2008, which was immediately followed by enrolment at RCA to take part in MA Ceramics and Glass, where he now teaches as an Associate Lecturer.

Much of his work is public facing and site-specific, such as a large-scale commission made for the University of Warwick, with projects in Bristol, Leeds and Kent in the pipeline – one of which including the repair of two Victorian tiled toilets. But ceramics, and notably tiles, are always present in his work, which also includes furniture made in association with the New Craftsmen. I spoke to him from his studio, now located just south of Paris, to discover more about his connection to and use of the material, which is almost certain to have a legacy in the near future and beyond.

JB: How and when did you first discover ceramic and at what point did you decide, or perhaps realise, it to be your primary creative practice?

MR: The ceramic studio at The University of Brighton was where I discovered and fell in love with clay. I was instinctively attracted to the light, ambience and teaching – tutor Alma Boyes in particular – and as an impatient 19-year-old, loved the immediacy of the material. The course focused on four materials, but ceramics shone through for me. I left with passion and a few good BA level projects under my belt, but discovered later that I was lacking in ceramic skills in comparison to contemporaries that had studied on a designated BA’s in ceramics. It was no bother long-term as I picked those up, but my time there was crucial in teaching me that I work best when ideas lead my work, instead of technique for example, and that hasn’t changed.

JB: Given it’s formable properties and rich history of 3D applications why have you tended to create 2D tiles? Although do you actually consider them to be 2D?

MR: A tile on a wall can be very flat, but it is an object when it’s in one’s hand pre-install. I love thinking about tiles in both dimensions and use my background in ‘slab-making’, which is a process of attaching flat sheets of clay together, to attach components to create bespoke corner or edge tiles – they are truly 3D. Tiles can cover and flow over a surface, and if that is a curved wall for example then you have something that challenges both dimensions. I enjoy exploring the words ‘clad’ and ‘cladding’ and how tiles ‘cover up’ and ‘wrap’.

JB: You mentioned the tiles being in your hands there, and you do put an emphasis on hand made tiles, which is obviously far more labour intensive than having them made with automated processes. What is the reasoning here and what do you feel it adds?

MR: My creation of tiles is always led by the idea and or client and brief. I love the process of making tiles and the planning and thinking that the design stage demands before clay is even touched. And it’s true that I am known for the start-to-finish process regarding the creation of tiles. But I also enjoy adapting that working method depending on the scale and budget of a project. To cover the 5 x 15m wall at The University of Warwick I needed to involve industry whilst also keeping ‘me’ involved in the making. This ended up including hand-made interventions into the factories production line. For a project at Rainham Hall in Essex there was no benefit to hand-rolling the tiles – the work was about how to create bespoke decorative designs onto the tiles using the garden – so we bought blank tiles from a factory in Stoke, so that our time and effort could go into the conceptual communal smoke-firing process.

JB: Narrative and story telling feature in some of your projects, not least the larger public pieces such as the mural for Warwick University you touched on there. How do you go about bringing this into your thinking and translating it through ceramics?

MR: The work with murals and site-specific pieces simply starts by visiting the location and chatting to the people involved. I’ll often get a feel for an angle to look into, and then a load of research follows, which I enjoy more and more. A new project in Bristol has me looking into the industrial activities of a very specific location next to a city centre canal and is totally fascinating. Who lived and worked there? How did things evolve? What was produced, and are there any scars from the enterprises etc? I often return to themes around community – new and old – and how people have shaped the environment in and around the site. Warwick was fun because the building – a new hub for all the Arts and Humanities subjects – wasn’t even built when I got involved.

The University took a big risk creating such an organic space regarding the layout and crossovers of staff and students, and I wanted that ‘chance’ to be referenced in my piece. It also influenced the title Faith in the Miraculous, as I imagined future meetings, conversations and the general cross-pollination that the building would harbour. With this in mind, I mixed and poured the glaze colour in such a way that the combination and resulting design can never be replicated. Risky for me and my team too, with a ‘one hit’ kind of approach, but it was true to the concept and energy of the wider project, so therefore led.

JB: Glaze, and with it, colour, are intrinsic to the majority of ceramics, and I’m intrigued as to how you go about choosing them. Not least with a project as chromatic as the one at Warwick University.

MR: Colour is something that occupies me more and more. Tiles are and have been coloured forever, so I’m in good company, but it is tricky for me as I find it joyous and freeing whilst also demanding of a justification and reason to use it. My wife, graphic designer Marine Duroselle, is very confident with colour and doesn’t understand my inner struggle, but I don’t have the background – Manchester is well grey! – and experience to simply pluck a palette and roll with it. A self-led project this year titled Congregate will allow me and colour to move with more fluidity, and I’m looking forward to that! However, for site-specific work, I believe that I need to reference and or ask the people and community who will live with the piece what they think. I needed twenty-one colours for Warwick – a lasting nod to Coventry being the UK City of Culture 2021 – and had to make my selection in lockdown without being able to get on their campus and to the local area. So, with lots of help, I came up with an online exercise that asked local people literally and metaphorically about colour in their area. The results were amazing, and the answers directly created a database of colour that I could then artistically choose from. For a new mural in Leeds, I focused in on a pallet of colour that was used by the Burmantofts Pottery – a local, now closed factory that produced influential works in the 19th Century. I guess I’m always looking for a related steer, and once I have the info, then that frees me up to use it how I see fit.

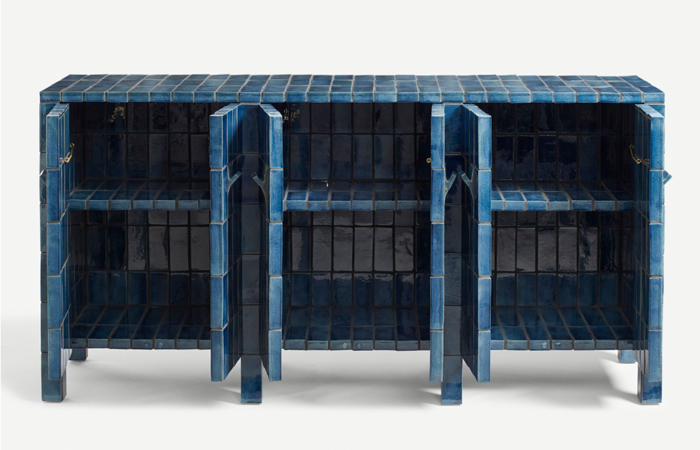

JB: I enjoyed seeing your work on display as part of the New Craftsmen exhibition at the London Design Festival last year, what’s the story behind the cabinet you showed? Is this a new departure into 3-dimensional objects and or furniture?

MR: My connection with TNC has been a long one. I’ve run bespoke workshops and experiences for them, and designed and executed a project called The Malleable Table with them back in 2015. But I wasn’t a maker of products or ranges so the work was sporadic. Then they approached me to create a commercial body of tiles. As part of that they asked if I’d like to make a piece of furniture to show alongside and suggested a table with tiles featured on it.

I had just had my ACE funded 2017 solo show entitled Clad and was obsessed with tiles covering entire surfaces including alcoves and corners and ended up creating The Welcome Cupboard. The range has grown from there, and for LDF last year we made The Welcome Drinks Cabinet – the biggest, most ambitious piece to date. Tiles wrap almost every surface, and the viewer or user is bombarded by the overall texture of the piece, and the variety of colour that comes from the hand-glazing technique I use. Stylistically, it’s not for everyone, but those who like it, really like it.