Jim Biddulph & The Seafood Industry

Set against a backdrop of concern regarding the devastation that rising sea levels will cause to low-lying landmasses; what shifts in oceanic circulation will have on the temperature and weather patterns of regions in the North Atlantic; the effects that plastic debris is having on marine life and the oceanic food chain; or the damage being caused to coral reefs around the globe, it’s hard to think of the sea as a viable natural resource and potential antidote to some of the challenges that we as a species will be faced within the 21st Century. But given the magnitude of the world’s oceans, and with it, the direct influence that they have upon the climate, perhaps it’s time we look at the ‘blue dot’ a little differently – a growing number of consciously driven innovators are certainly doing so.

Forming part of the wider trend for reconsidering the waste management of existing industries, a number of designers are turning their attention to the seafood industry. For whilst the debate surrounding the fishing of our oceans (notably over-fishing) continues, the consumption of food from the sea still endures and with it comes a great deal of unused natural resources. Each year between 6-8 million tonnes of waste is produced by the industry from crustaceans alone. As with so much of the waste we create, albeit in diametrically opposed surrounding to their origins, those shells tend to end up in landfill. And because shells are naturally designed to protect, they are made of tough materials; predominantly calcium carbonate and chitin, and as such will remain in a landfill for some considerable time. But the positive characteristics of these natural materials have not gone unnoticed by designers who are looking to create novel ways of extracting shells from the waste stream and transforming them into new, useful materials.

newtab-22 go to the source and collect shells from seafood restaurants in Seoul and London and then transform them into concrete-like materials. The beauty of the Sea Stone project is that the high content of calcium carbonate, which is essentially limestone, gets put to good use in creating the durable but ‘clean’ biomaterial. The shells themselves are ground into fine particles and mixed with an array of natural binders, which creates rigidity, hardness and texture. In many ways the process mimics that of the creation of the earth’s crust, only at a much faster pace and without directly adding more waste substances in the process.

As we’ve reported, initiatives such as Everyday Plastic have drawn attention to the over abundance of plastic waste and severe lack of means with which to properly recycle it, but The Shellworks have invented an alternative solution. Once again, they seek to upcycle crustacean shell waste, but turn their attention to tackling one of the biggest plastic problems – packaging. Having developed a variety of material recipes the team can create a range of bio-plastics using specially designed equipment, which allows them to control and adapt the appearance, mechanical properties and barrier performance of the materials. Not only that, the materials can be composted at home and degrade in 4-6 weeks – perfect for the short-term functional requirements of packaging.

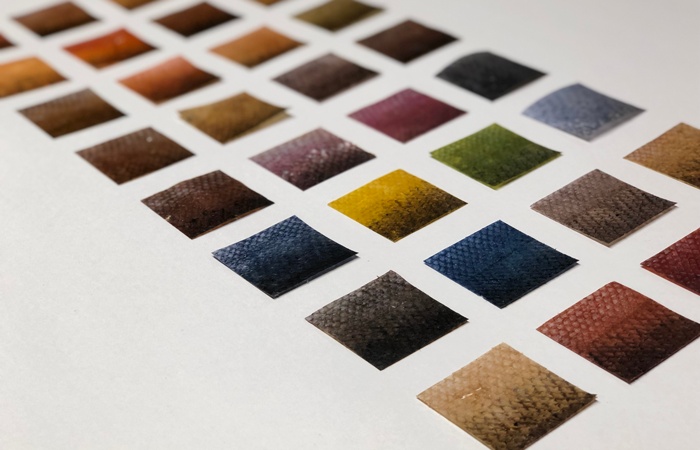

The seafood industry creates more than just waste shells. Fish, notably Salmon, are still a popular dish on many a menu and Designer Andrea Liu looks to transform salmon skin, a by-product of the smoking process, into an alternative to leather. In the process of cleaning, tanning, dyeing and weaving the discarded skins she elevates their value from both an economical and functional perspective. Having initially been inspired by Alaskan Native American methods the patterns of the weave are also reminiscent of those you’d find on traditional fisherman’s jumpers or ganseys, linking the visual narrative back to the origins of the materials themselves.

As well as utilising leftovers and by-products of the sea, designers are also recognising the incredible potential for growing and manipulating natural substances that the sea offers, with one organism capturing the imaginations of a number of designers more than any other – algae. It’s hardly a surprise when you consider that algae consist of an incredibly diverse group of organisms that are prolific in their reproduction and therefore abundant. Because of this they also offer a host of amazing properties, something design studios such as AlgoteK are starting to recognise and capitalise upon. Much like The Shellworks, the AlgoteK team, who are based in Oregon in the USA, have devised a method of creating biodegradable plastic alternatives. By literally growing algae and transforming it via production methods that create no hazardous or damaging waste they’ve also created a fully renewable solution. What’s more, during the process of its growth, the algae draw out carbon dioxide from the atmosphere and because the algae can be grown in pretty much any saltwater, the material can in essence be produced anywhere, which greatly reduces the carbon footprint required in transporting it from it’s production site to place of use.

Tel-Aviv based designer Daniel Elkayam shares a similar interest in algae, although a recent collaboration with Polish interior design brand OVO Design has moved his inventive bio-based sheet material called SEAmpathy towards the interiors market. Using Biophilic Design principles, Daniel has created organically shaped timber cut-outs with which frame his speckled algae derived material, turning them into decorative wall panels that sit somewhere between art and design. In contrast, a team of professors who form part of the Bio-ID lab at Bartlett School of Architecture have utilised algae for a very different but pertinent purpose. In discovering that up to 80% of India’s groundwater is polluted as a result of the country’s prolific textile and jewellery industries, the group recognised that a bioreactor that can clean water through bioremediation was required. Cue algae, which they have included in a hydrogel placed in the veined channels of the Indus Tile. Inspired by the veins of a leaf, contaminated water runs down the surface of the tiles and through the channels, where the algae works it’s magic in sequestering pollutants like the heavy metal cadmium from the water, which now clean, is collected and redistributed.

Seaweed is another plentiful aquatic plant and whilst many of us wouldn’t realise it, perhaps because of its size and density, it is in fact an algae. Copenhagen-based architectural technologist Kathryn Larsen is no stranger to the plant and has been researching ways in which to bring the traditional Danish building method of seaweed thatching into the contemporary construction market. Once again, growing seaweed, in this case Eelgrass is a carbon negative process and as such the timber-framed panels offer a sustainable roofing and insulation solution. Whilst vernacular in style, the idea that materials can be sourced and crafted locally is a core driver of the project and helps to underline the fact that the natural material is rot and fire resistant and non-toxic.

It’s a perfect example of the fact that most of the materials that we can harvest from the sea, be they from plant or animal life, are natural super-materials.