Material: Concrete with Jim Biddulph

Whilst there are various material ages of humankind, the Stone Age, Bronze Age and the Iron Age to name a few, there is one material that not only built an entire empire, but literally laid the foundations for all of those to come.

That material is concrete; a composite discovered some 8500 years ago and used in earnest by the Romans until the fall of the empire. Whilst its usage fell dormant for hundreds of years following this, concrete is now the most commonly used material based on tonnage on the planet, it’s use in the modern world only exceeded by naturally occurring water.

The ascent to material superstardom is thanks to a development made by Joesph Aspdin here in the UK in 1824. A composite by definition, concrete has always been made up of coarse aggregate and some form of fluid cement. When activated by water, a chemical reaction occurs that transforms the individual parts into a hard matrix, forming a stone like material in the process. Aspdin discovered that cement extracted from the Isle of Portland in Dorset made beautifully fine slurry when mixed with water and created a surface finish akin to Portland stone when set, and thus Portland Cement was invented. Concretes high compressive strength and density, coupled with its workability made it the ultimate artificial rock, a new viable alternative to natural stone.

From there on in, concrete became the go-to building material and in 1849 another Brit, Joseph Monier realised that it could even be reinforced with rebar to make super structures. Cue some of the greatest feats of engineering of the 20th century, including the Hoover Dam and the Panama Canal; an architectural movement that still divides opinion today in the Brutalist forms of the middle of last century; as well as countless foundations, silos, walls, pavements, pipes and surfaces.

Whilst concrete becomes almost invisible in it’s ubiquity, surface designers are still discovering unique and exiting ways to bring the material to life. One of the notable characteristics of the material that suits surface designers and manufacturers alike is its ability to be poured and moulded. Graphic Relief’s engineered surfaces harness state of the art moulding technology to create textures, surface effects and imagery of photographic quality that defy all logic in transforming a hard, cold and inert material into a mind-blowing surface of intricate detail. Working collaboratively with clients enables them to realise their creative vision, and whilst they often start with flat digital images, the cast surfaces that they produce are anything but that. Often mistaken as etched and/or 3-D printed, all the magic in making the indented and raised surface effects actually all occurs in the meticulously produced moulds; a testament to how much detail concrete can in fact yield.

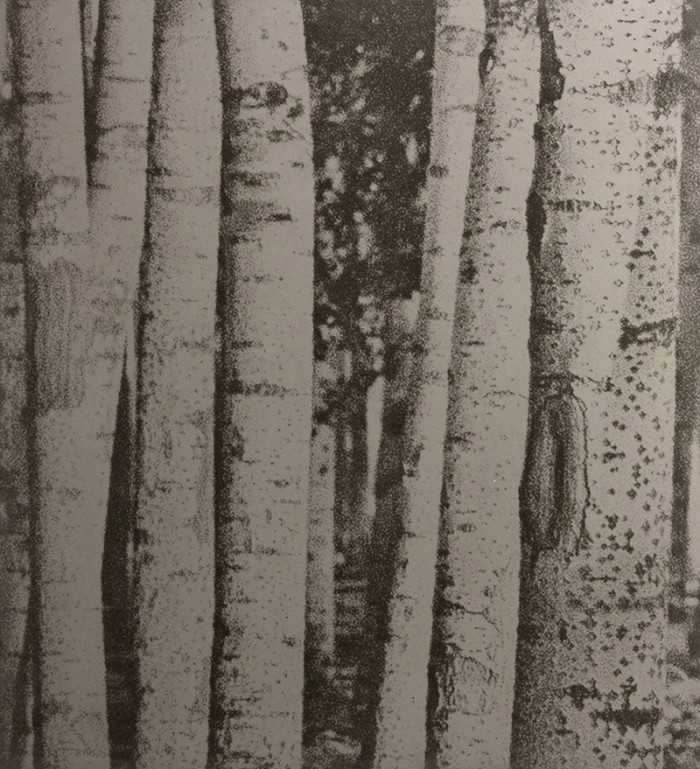

Such is the detail that they can produce, Graphic Relief has been used on major art, design and architectural projects alike. The Ogham Wall, an artistic depiction of an ancient Irish language that has its origins in the 4-6th Century AD, was produced in collaboration with Grafton Architects for the London Design Festival and installed in The Tapestry Room at the V&A in 2015. Working with cast concrete the monumental alphabet wall was comprised of 23 detailed ‘fins,’ each being nearly 3m tall. Hand crafted and using specialist moulds the slabs referenced the bark finishes of fir, birch, elder & holly, all native to Ireland, in stunning detail. They have also worked with Rut Blees Luxemburg and Lynch Architects to create The Silver Forest at Westminster City Hall. 16 concrete panels, depicting a photorealist scene of a silver birch forest at night, join to create a 7x30m artwork that subtly changes as the light of day travels across the textured concrete surface.

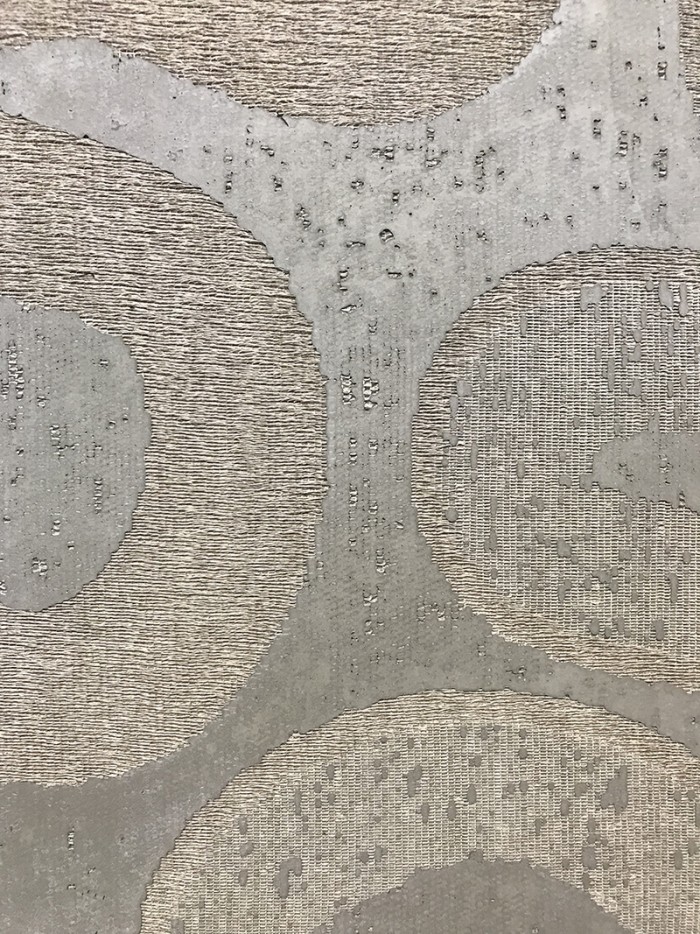

Ruth Morrow and Trish Belford are no strangers to the versatility of concrete, and have long been catalysts in pushing its potential beyond our presubscribed expectations. Having formed Tactility Factory back in 2007 they’ve become experts in infusing concrete with textiles to create beautiful hybrid surface materials.

Ruth and Trish first met over lunch one day at Ulster University, where they both worked at the time. A love for both architecture and textiles quickly surfaced and it wasn’t long before they were working together to see what could be done with their two favourite material groups. Having applied for a small Arts Council grant they purchased a concrete mixer, called Billy (it was orange) and took a step into the unknown. As Trish recalls, their collective thinking offered a unique balance, “Ruth’s view of textiles was refreshing as she felt architects treated textiles as the subservient dressing on the surface as opposed to be a part of the surface. Whilst I was keen to explore and express tactility in the built environment.”

Having secured a number of prestigious jobs in Cairo, Abu Dhabi and Dubai the design duo are once again exploring new and unknown avenues. Working collaboratively with MYB textiles in Scotland they’re setting up an entirely new research project. They’ve secured an AHRC research grant with the aim to diversify the traditional weaving methods used by MYB. Experimenting with linen yarn, the pair are designing brand new textiles suitable to be embedded in concrete. The designs are being sourced from the archives of William Liddell, who in their heyday, were the most influential damask weavers in Northern Ireland; exporting globally as well as weaving the linen damask used on the Titanic. Queens University Concrete Lab, where Trish now works, has joined in the collaboration with Ulster University where Ruth still resides. Its primary aim is simple; to discover just how much they can do in combining these two apposing materials. They’re already beautiful and beguiling material that begged to be touched, so we’re excited to see the results!

Explore more materials with Jim Biddulph