Sustainability By Design

The Zollverein industrial complex in Essen, Germany, comprises of an imposing set of largely red brick and steel buildings and structures built in the 19th and 20th centuries. It was once a hive of heavy industry, driven by the coal mines within, but is now considered a monument to the Industrial Revolution with certain parts listed as UNESCO World Heritage sites for being noteworthy examples of Bauhaus-inspired modernist architecture. Having been decommissioned in 1986, the complex is now home to art, culture, gastronomy, and the Folkwang University of the Arts.

With the latter, its legacy for harnessing materials is being reimagined for the 21st century, and new, sustainable approaches to industrial development are being explored. This new departure is led by a disruptive collective known as SBYD.SPACE (Sustainability By Design), which is formed of four research groups: SPACE FOR NARRATIVE, SPACE FOR REPAIR, SPACE FOR TEXTILES AND SPACE FOR BIOMATERIALS. During Dutch Design Week the team put on their first collaborative exhibition – appropriately titled Spaces for Tomorrow – showcasing 18 projects that “explore new climate-neutral and resource-light ways of living and production.”

During the event, the SPACE FOR NARRATIVES team introduced a kiosk at the entrance from which they hosted talks, distributed zines, and invited guests to share their visions for the future by posting them through a letterbox. Constructed from readily available scaffold poles and recycled plastic sheets supplied by Polygood, the kiosk typifies the collective desire to explore “The capability of design in making theories and abstract concepts tangible – and transferring them into everyday life.”

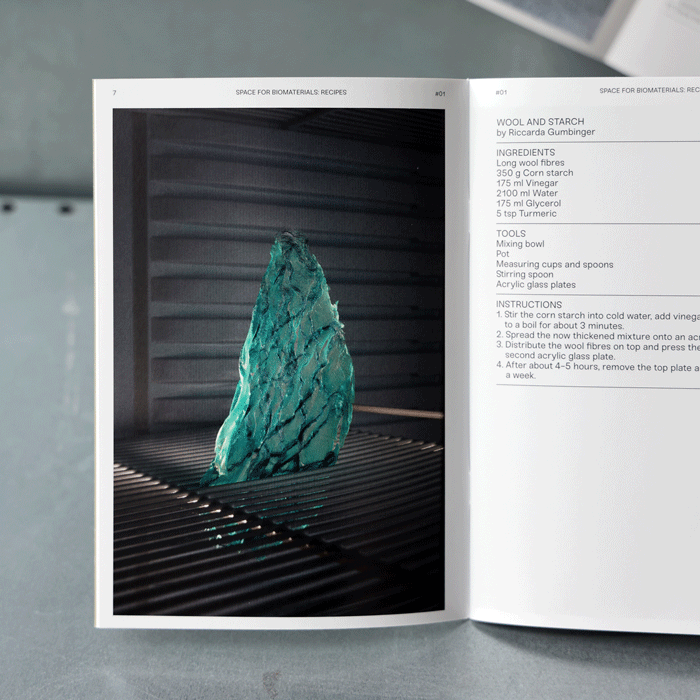

Positing, discussing and testing ideas in practice with diverse audiences and collaborators is the common thread that runs through each of the four groups, with a shared desire to discover sustainable alternatives a core tenet of them all. This practice is underlined by the SPACE FOR BIOMATERIALS inaugural offering, which includes a free zine of 16 material recipes. Working at the intersection of design and materials science, the team of design students was prompted to undertake an experimental research-through-design process in the university’s new Bio Lab, with the aim of producing alternatives to petroleum-based materials. This open approach invites any inquisitive reader to play with the recipes themselves, with clear ingredients, tools and instructions laid out alongside beautiful imagery of the team’s own experimentation. The constituent parts are varied but generally easy to get hold of, and include the likes of invasive Japanese Knotweed, wool, starch, algae, seaweed and apple. The results are equally varied, with an array of tantalising forms, textures and properties made possible by some unconventional variations on cooking, which include boiling in detergent, simmering in glycerol and whisking with spirulina.

But it’s very much the questions that they pose that resonate the loudest and open new possibilities for collective action, a few of which include:

“What if a product is not meant to last? Could it then become beneficial to bacteria, fungi and plants in soil? How can such a regenerative, post-human use be incorporated into a product’s design from the outset? And by embracing bio-based materials, can designers develop an aesthetic that celebrates imperfection and ephemerality?”

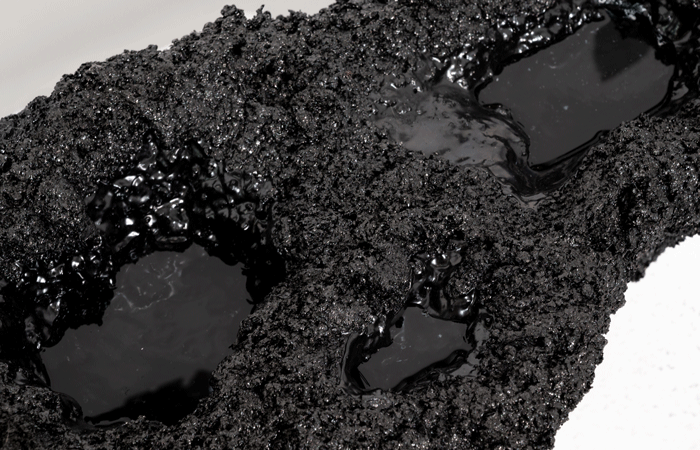

Many of the designers involved have taken their recipe formulations further, creating contexts for their output by manipulating their forms and introducing potential functionality. Recent Designer in Residence Lapatsch | Unger’s project Habitat investigates how new material developments might allow for co-existence with other species. By combining biochar derived from biogenic residues through pyrolysis with a pine resin binder the design duo has created a collection of other-worldly archetypes. The unique material “is condensed, but not unchangeable (and ) the objects have tendencies that are inherent to living systems: the ability to change, to decay and to return to nature as nutrients.” When nestled within the natural landscape the sculptural forms therefore encourage interaction and co-habitation with all living forms.

Fellow Designer in Residence Lilli Malou Weinhold’s project Metallophytes: Echoes Of Extraction is also concerned with residues left behind in the earth, but is instead focused on the heavy metals found in soil. As we covered in our Cherished Earth article last year, pollution generated by agriculture, industrial activity, and air pollution is contaminating and degrading soil at a rapid rate, causing a damaging effect on the natural world and the ecosystems it harbours. Heavy metals are one of the core by-products of these activities, with record numbers found in soil across the world, although some very rare plant species known as metallophytes can survive under these torrid conditions. It’s here that Weinhold has taken her cue, creating plant ash glazes formed from the pollutants absorbed and extracted from these toxic-tolerant plants. While entirely functional, Weinhold sees the ceramics created in the project “as poetic archives, transforming environmental data into tangible objects that highlight the lasting legacy of industrial pollution. By using glazes formed from heavy metal pollutants, the work aims to raise awareness about soil contamination, often overlooked, and the critical role of metallophytes in transforming toxic environments into sustainable ecosystems.” The seemingly tarnished bowls on display, along with an accompanying book, represent a fitting project for the former industrial powerhouse it has quite literally been born out of.

Lilli Seiler’s Eggshell Plant Pot project also seeks to tackle soil degradation, but where Weinhold aims to create awareness, Seiler instead hopes to enrich the soil and encourage a broad and healthy array of plant growth. As the title of the project suggests, she intends to do so using food byproducts in the form of eggshells. Rich in calcium and micronutrients such as potassium and magnesium, as well as being formable once ground down, eggshells are an ideal material for creating biodegradable plant pots. The beauty of which being that having diverted waste, they also give back to the earth at the end of their life cycle, thus closing the loop of production.

Mycelium, the root-like structure of fungus, has been on the rise as an alternative biomaterial for a few years now, although often in the form of objects and surfaces “grown” from composite materials that also contain wood waste or straw. Designer Paulina Heidlberger however explores the possibility of fungi as a veneer with her range of Fungiture. The surfaces she creates require no adhesive, instead using heat to press mycelium-based materials onto wood, creating entirely unique objects in the process.

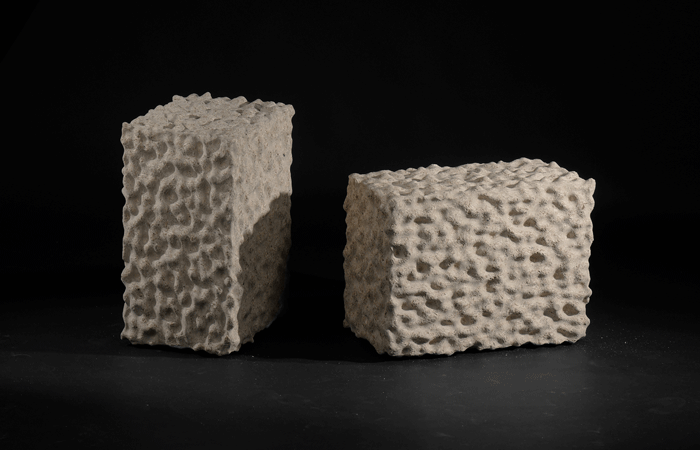

Whereas, SPACE FOR REPAIR participant Debora Weusthof takes a different approach to materiality in the creation of her furniture product, Cracker. As opposed to biomaterials, she explores existing waste streams, giving a new lease of life to chipboard panels. Due to the granular size of the wood particles and the abundance of glue used in its production, chipboard has always proven difficult to effectively recycle. Add to this that they become almost entirely redundant if the veneered face is damaged and you have a material that almost exclusively ends up in landfill or the incinerator. But Weusthof’s contemporary twist gives such boards the chance of a second life. By embracing modern technology she has developed a process whereby the sheet can be opened up and CNC milled to create a new and aesthetically appealing surface texture and finish…not unlike that of a cracker.

These projects represent a seismic shift in approach to materiality from those applied so dominantly over the previous two centuries at the Zollverein site. As we increasingly see and feel the after-effects of those damaging processes – which are indicative of the time, not just this site – it feels more important than ever that revisions such as this are given the time, space and funding to experiment with and develop new forms of planet-positive material production. With it, there is some hope that we can heal some of the damage caused – while retaining the spirit of development – from that revolutionary period.